TESOL Convention - Toronto - Friday, March 27, 2015

Here are highlights from the four sessions I attended on the second day of TESOL.

Transitioning to College Writing: Language Use and Sentence Level Skills

This workshop involved a series of presenters, all who focused on the issue of supporting students' linguistics needs as they develop as college writers.

Ditlev Larson from Winona State University used the experiences of three students (from his larger study of freshman L2 writers) to highlight the gap between the way language issues are addressed in high school writing classes and the language expectations in college. All three students stressed that they felt unprepared to meet the new and more sophisticated linguistic demands of their college classes. Larson suggested that the concern over "deficit thinking" in high school and even college writing classes has led many teachers to avoid focusing on sentence-level issues, but he asked, "Are we doing students a disservice by not focusing at all on sentence-level issues? If the expectation is there, where and when should it be taught?"

Dana Ferris discussed how her institution, University of California-Davis, has begun to incorporate language development into their FYC (first year composition) program. Ferris began with the challenges the FYC program faced--an extremely diverse student population, a teaching staff not trained in ESL, a packed syllabus, and a broad range of student needs. Ferris and her colleagues wondered, "How can we have a more integrated, organized approach to language?" The answer was adding "guided self-study" to the curriculum. Students could pursue one of three options: Self-Directed Vocabulary Journal, Grammar-Mechanics Self-Study, or Style Analysis Journal. The materials for each of these options were provided (and didn't have to be developed by the teachers) and the students did the work outside of class. Ferris discussed how this Language Development Program (LDP) has evolved over the last three years and she also shared student feedback.

Similarly, Sarah Snyder, a graduate student at Arizona State University, shared her experiences teaching English 194, a one-credit "walk along" course that supports students with their language development in first-year composition courses. The course uses a required textbook (Ferris's Language Power) but students create a plan of study and also receive individualized instruction.

Finally, the last two presentations focused more specifically on the writing of multilingual students.

Scott Douglas, from the University of British Columbia, analyzed the vocabulary (lexical profiles) of students' final essays in a university-level non-credit academic writing class while Nigel Caplan and Ken Cranker assessed the sentence-level strengths and weaknesses of students' exit essays that earned a passing score.

Crossing Borders in Multilingual Classrooms - Using Students Funds of Knowledge

In this interesting session, Cathy Amanti from Georgia State University and Lori Edmonds from Montgomery College introduced us to the idea of Funds of Knowledge and discussed how this concept could be used in a variety of ways in the classroom. On a series of PowerPoints, they defined Funds of Knowledge and gave examples.

|

| Funds of Knowledge - What it is |

|

| Funds of Knowledge - What it isn't |

|

| Some Examples |

Amanti and Edmonds argued for the value of continuing to use this concept to counteract the more common "deficit" model used to describe households of working class and/or linguistic minority students. They suggested that teachers of multilingual students need to use what students already know and/or have access to--home language "oracy and literacy," their experiences with translation or interpretation, and/or home/community literacy practices.

Amanti and Edmonds then gave us some examples and exercises to do to help us see how Funds of Knowledge might work in practice. First, they showed an example of an activity that definitely did not use this concept--a quiz question that used a skiing analogy. In this case, the teacher didn't realize that not all students would have knowledge of or experience with this activity. However, the positive examples all focused on ways teachers could utilize knowledge that individual students had or could obtain in order to learn or apply new concepts. For example, a math teacher asked a student to talk to her mother, a seamstress, about how she figured out how much fabric was needed for a skirt. The teacher than used the knowledge the student had discovered to write an algebraic equation, showing the student that her mother was actually using algebra. Another example they gave was about a student with weaker language skills taking a leadership role in a middle school math club because of his experiences building structures in his home country.

Though this presentation focused more on K-8 examples, the connections to college classrooms are exciting to think about.

The Role of Language in Preparing Teachers to Teach Writing

In this workshop, five presenters did an excellent job of showing how Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) and genre-based pedagogies could work at every educational level from early grades through college and what implications this has for teacher training.

Sylvia Pessoa from Carnegie Mellon University-Qatar started the workshop by giving an overview of important concepts. She described language as a "meaning-making resource influenced by context" and referenced the social theory of language developed by Halliday (1976, 1984). She defined Systemic Functional Linguistics (SFL) as "language driven tools for the analysis of academic writing and writing development." She also introduced the idea of a Teaching & Learning Cycle when it came to helping students learn academic genres--deconstruction (the teacher and students take apart a text genre to see how it works), joint construction (the teacher and student write examples of this genre together) and independent construction (the student creates texts on her own). According to Pessoa, this cycle helps students understand genre expectations before writing, provides them with tools to talk about the language needed, and makes the language of school explicit. Not surprisingly, teachers need to go through this process as well in order to fully understand the genres they have to teach and that is the overall purpose of this workshop--thinking about ways to help teachers develop the linguistic knowledge necessary to use both SFL and genre-based approaches.

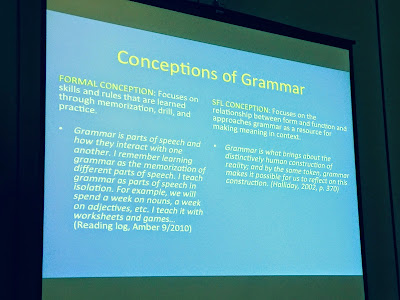

In the next presentation, Meg Gebhard discussed how she works to shift pre-service teachers from a formal idea of grammar to having an SFL orientation towards grammar, where form and function are combined:

As part of her presentation, Gebhard facilitated an activity where we looked at sample e-mails (students writing a teacher about enrolling in a course), talked about the genre in general, and then looked specifically at register issues in one specific e-mail:

This act of register analysis involved looking closely at the language choices each writer made and determining "what linguistic choices make a 'good' e-mail request"--one that gets the job done. The activity we engaged in resembles the type of linguistic analysis that Gebhard had her pre-service teachers do for all sorts of genres that elementary and middle school students are expected to learn. At the end of her presentation, Gebhard shared several quotes from teachers that showed how their view of grammar had changed and how that affected their classroom practice.

In her presentation, Mary Estela Brisk talked about how discussions of genre and language go together and the need for both teachers and students to break down academic texts in order to see how to construct them effectively. This deconstruction process often needs to focus specifically on linguistic elements in order for students (and their teachers) to learn “the particular role that parts of language play in genres.” Brisk demonstrated how she works with pre-service teachers by asking us to look at a very short “model” text to determine genre conventions and then a student sample to see what they might need help with in meeting those conventions.

In the final presentation of the workshop, Ryan Miller from Kent State University, Thomas Mitchell from Carnegie Mellon University of Qatar, and Syvia Pessoa discussed how concepts of genre and SFL could could be used in a university context—especially related to WAC efforts. They shared insights from a research project at CMU-Qatar, focusing on 85 students in a history class who were writing source-based texts. One of the questions they explored related to a specific feature of argumentative writing in this discipline—how did writers expand or contract possible voices in the text? They shared two student samples with the audience, one noticeably stronger than the other, in order to show us the complex nature of argument in history texts. Like the other presenters, they emphasized the need for teachers to help students understand the genres that they are expected to produce through a process of deconstruction, collaborative construction, and then independent construction. If more faculty deconstructed the genres they assigned, they would be better able to make genre expectations explicit to their students.

A Center of One's Own - Creating an IEP Tutoring Center

In

the last session of the day, Angela Lehman from Virginia Commonwealth

University talked about the benefits and challenges she faced in creating a

tutoring center specifically for an Intensive English Program (or IEP). She mentioned that VCU has both a writing center and an academic tutoring center, but these programs did not meet the varied needs of the 350 students enrolled in the English Language Program. The benefits and challenges she mentioned sounded awfully familiar. As a writing center person, this was an interesting session to attend because it reminded me that academic support can take all sorts of shapes and writing centers can't necessarily do it all.

Did you get examples of what Dana Ferris' three LDP modules look like? I find the bit you wrote about it here to be very appealing.

ReplyDeleteI only have the book, Language Power, but I was going to e-mail her about this.

ReplyDelete